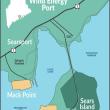

Mack Point or Sears Island: Debate over state offshore wind port site continues

SEARSPORT — The geographical distance between Mack Point and Sears Island on the northern end of Penobscot Bay is but a slingshot apart, but the gulf between the advocates for, and opponents of, siting an offshore wind port and assembly facility on Sears Island is sizable.

Maine’s proposed Dirigo Atlantic Floating Offshore Wind Port is the largest — financially and environmentally impactful — potential development on Penobscot Bay that the state has considered in decades.

In May, the Maine Department of Transportation, which is leading the planning efforts, applied for $456 million in federal grant funding to help the state construct the East Coast's first floating offshore wind port on initially 100 acres of Sears Island. That 100 acres is a portion of 330 acres that the State of Maine set aside on Sears Island in 2009 for development. The other 600 acres of the 941 acres state-owned island was set aside in a permanent conservation easement held by the Maine Coast Heritage Trust.

Lines have been drawn by those wanting to keep Sears Island undeveloped versus those who want to build a wind port on the island. The latter includes labor and environmental groups that support a Sears Island wind port project in order to advance renewable energy resources.

But there is a third element to the debate, raised by Sprague Operating Resources.

Sprague owns the already industrially developed Mack Point and wants the state to consider repurposing its 100-plus acres as an alternate site.

Officials from the New Hampshire-based company propelled their intent into the public eye June 11, offering tours of its Mack Point facility. The company has submitted its alternate wind port plan to the DOT and is advocating for it before the state, as well as federal regulatory agencies that will review Maine’s plans.

“We think this is a viable alternative,” said Sprague’s Vice President of Materials Handling James Therriault, speaking before a group of reporters June 11, at Mack Point. “We’ve had this looked at by marine engineers. We want the state to use a third party, an objective party, to compare the costs of the two facilities and the environmental impact of the two facilities, using our modified plan. Not the original Moffatt and Nichols plan that came out a couple of years ago.”

Sprague could get a third party to analyze the Mack Point plan in comparison to the Sears Island plan, “but then they [the DOT] would just say that is self-serving,” he said.

On June 24, the DOT said in an email statement: “MaineDOT will continue to evaluate both Sears Island and Mack Point, as required by the NEPA [National Environmental Policy Act] process. The NEPA document is an environmental impact statement, and we still don’t have a lead federal agency. This is going to take some significant time to complete.”

Why Mack Point?

The privately-owned Sprague Energy wants to lease its Searsport terminal land to the state, a longterm real estate deal that would help a company already in the business of unloading land-based wind turbines from ships that tie up at Mack Point, having sailed in from as far away as India. Sprague offloads the turbines, stacking them for truck transport to wind power sites scattered around Aroostook, Franklin, Hancock and Washington counties.

Sprague established its company in 1870, first with coal, then supplying oil and gas and other materials to markets. Its port terminals lie along on coast from New York to Maine, with one more on the St. Lawrence River in Canada.

In 2022, Sprague was acquired by the New York City based Hartree Partners, which trades in the financial energy and commodities markets. Hartree itself is owned by the company’s founding partners, senior staff, and certain funds managed by Oaktree Capital Management, LP, an asset firm.

Sprague said in a news release: “Hartree’s global reach and financial support allow Sprague to expand and enhance the company’s existing infrastructure and businesses, supporting society’s transition to sustainable forms of energy.”

Like the State of Maine, those companies are focused on new energy sources. Maine wants to advance clean energy production, specifically wind power; “however, this energy cannot be harnessed and will remain offshore without significant investments in new port infrastructure that can support the massive and unique infrastructure necessary to accommodate floating offshore wind turbines,” the state said in its recent application for federal funding.

Sprague also recognizes the opportunities of offshore wind, which is projected to overtake land-based wind power because of its increased wind speeds and ability to generate more power. (See current locations of Maine’s land-based wind turbines.)

Offshore wind is big business with the Biden Administration’s focus on renewable energy production. The U.S. Dept. of Energy said in April: “The U.S. offshore wind market is at an inflection point. Despite facing macroeconomic challenges, the sector is adapting, and improved risk mitigation is being built into industry planning. State leadership has been and will remain fundamental, as will federal policy, including use of long-standing tools and new resources made available through the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and the Inflation Reduction Act.”

At the end of April, the federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management announced its first-ever offshore wind energy auction in the Gulf of Maine Wind Energy Area that would include eight lease areas offshore of Maine, Massachusetts and New Hampshire, “totaling nearly one million acres, which have the potential to generate approximately 15 GW of clean, renewable energy and power more than five million homes.”

On June 21, the federal government issued its requisite draft environment assessment for commercial wind leases in the Gulf of Maine, with deadline for public comments set for July 22. The EA determines if a federal action has the potential to cause significant environmental effects.

“The EA will consider project easements and grants for subsea cable corridors associated with leasing,” according to the federal register, where federal public notices are filed. “The EA will also consider the potential environmental impacts associated with site characterization activities (i.e., biological, archaeological, geological, and geophysical surveys and core samples) and site assessment activities (i.e., installation of meteorological buoys) that are expected to take place following lease issuance.”

Maine fits into all of this with its intent to build, “the first purpose-built floating offshore wind port on the East Coast to meet growing demand for offshore wind infrastructure,” according to the grant application.

In 2022, Maine retained the Long Beach, California-based Moffatt and Nichol to assess possible wind port sites and produce a preliminary plan. And with a coalition of environmental, labor, and economic organizations behind it, the state said in February 2024 that Sears Island was the logical spot.

But Sprague says, not so fast.

On June 11, Sprague hosted three tours at its 140-acre Searsport industrial site. Billed as an open house, the invitation was widely circulated as an opportunity for: “a close up look to see utility scale wind energy component handling and learn more about Sprague’s lower environmental impact floating ocean wind terminal design. Guests will be able to see large utility size nacelles (cover housing for all generating components in a wind turbine) towers and blades destined for two land- based wind projects currently being constructed in Maine this year.”

“We’ve got two goals here today,” said Sprague’s Therriault. “One is to introduce you to the terminal, all the things we currently do and all of which we will still be able to do, which is in our plan. None of that is going away as part of this plan we have come up with. The second is to explain our lower impact alternative.”

The Mack Point plan

While the Sears Island port plan hovers at $760 million, the Mack Point alternative has been estimated at $510 million, said Therriault.

Last year, he participated in Maine’s wind port site selection process with the DOT and others as a member of the Offshore Wind Port Advisory Group. Therriault said he met before the meetings with state representatives and showed them Sprague’s plans.

“Unfortunately, they [the plans] never came out in what was the official process, so immediately following what turned out to be the last meeting of the advisory group I sent the entire advisory group these plans last summer,” he said.

Therriault said representatives of Moffatt and Nichols did meet with Sprague.

“We worked very early on with the state to try to have the alternative here, but unfortunately what ended up coming out of that was that Moffatt and Nichols took the state’s plan for Sears Island and as a postage stamp, slid it over here, put it where they wanted to put it — put the same dock where they wanted to put it — and the net result was, they put it in areas that did not have a lot of natural depth. They put it in areas that had standing fresh water, and in areas over the tanks we currently use. The result is something that says, ‘Ok, to get this done, there is going to have to be 500,000 cubic yards of dredging, impact on wetlands, and the risk of something under those tanks.”

But Therriault said Sprague instead took the state’s data for various designs associated with a wind port facility, as well as data from the University of Maine for its floating turbine foundations, and configured a different layout, one that reduced dredging to 73,000 cubic yards.

Sprague’s engineers asked themselves, said Therriault, “Is there a way to use Yankee ingenuity to figure out the best way to get this done.”

Sprague emphasizes three reasons to favor Mack Point: Existing infrastructure and expertise, continued protection of habitat on Sears Island, and cost efficiencies associated with an, “85 percent reduction in dredging from original plan and quicker path the permitting.”

The plan they produced last summer was sent to the state, he said, adding: “Based on the anecdotal information out there from the announcement from the state [made in February announcing Sears Island as the preferred location], it looks like they have not looked at an alternative plan.”

Highlights from the plan, as written in a Sprague news release, include:

“100 acres segregated from all current activities with its own dedicated entrance.

“Dedicated Vessel Component Receipt Dock: Already dredged to 35 feet of mean low water.

“Dedicated Base Launching Dock: Allowing the use of a semi-submersible barge or tug dock device.

“Dedicated Base Assembly Area: out of the flow of the rest of the facility.

“Dedicated Fit-Up Dock for Wind Energy Component Assembly: Separated from the launch dock, decreasing conflicts when lifting blades; allows for use of large assembly cranes to move ultra-heavy components.

“Greatly Increased Docking Space: More total dock face than the current Sears Island design with 1,600 feet dedicated to large vessels and foundations, while providing an additional 1,000 feet for small work boats and tugs.

“A Second Large Vessel Dock: For Sprague’s current bulk and liquid operations while also doubling as an additional backup component receipt dock for components using a self-propelled motor transporter.

“A Designated Support Services Area: An area away from the workflow for employee parking, warehousing of critical supplies, and administrative offices and work trailers.

“An Additional 10-acre Full-Function Rail Yard: Already existing rail yard and lines throughout the terminal. Rail system has recently undergone a $2 million renovation allowing for the delivery of domestically sourced components and supplies, while not interfering with other wind handling activities.

“Ready to Adjust to Wind Energy while Preserving Current Capacity: Sprague will relocate current terminal activity to accommodate offshore wind development with no decrease in capability.

“Construction Time and Costs Reduced: Sprague’s total cost is expected to be less than either Moffatt and Nichols plan, and, its already industrial nature creates less risk of delays in permitting.”

Sprague has two existing docks, bulk and liquid.

“We’ll dedicate our liquid dock to the project,” Therriault said.

The bulk dock would be refitted to accommodate liquid, as well, “so we will actually increase our functionality,” said Therriault. “It will allow us, or Irving, to bring in fuel vessels.”

Standing before large renderings of a proposed Mack Point layouts, he outlined of how the turbines could be assembled at Mack Point, and then towed out to their offshore locations.

“Any plan has to have the ability to have this construction, this launching, this fit-up,” he said, as well as the ability to bring the components in. That includes docks and rail, the latter because more components for turbines are being manufactured in the U.S., he added.

He emphasized the updated dredging estimates, down to 73,000 cubic yards from the original 500,000 cub yard estimation. That reduction would the Mack Point cost by $50 million, said Therriault.

“Most of the environmental groups have said they would support responsible dredging of that size,” he said. “I don’t think you’ll have the same opposition you had in the past.”

Some of the large fuel tanks would be removed from the Sprague land, and dedicated to the wind power facility. Some tanks would be saved because, as Therriault said, there have been projects proposed in Maine for making renewable diesel fuel from wood fiber, which would then be loaded onto barges and transported south.

“We kept those tanks out of the [wind port] plan so we had that capability,” he said.

A piece of land currently in field would be dedicated to parking for the projected 300 employees, a spot that would be used for depositing dredge spoils and paved over, said Therriault.

If the wind port were to be sited at Mack Point, Sprague would fill in shoreline to accommodate heavy equipment. The same infill process would apply to Sears Island, said Therriault. The grant application for Sears Island notes that soil would be excavated from the island’s upland to fill in the waterfront.

Sprague said it would lease land on Mack Point to the state for 25 years, or longer, but no lease rates have been discussed.

“There would be some kind of lease payment, but now, if we take $50 million out of our equation [cost of dredging reduction] — and since last summer, the state’s price tag has gone up by $100-$150 million — let’s look at the final comparison and maybe there is $150 million delta between the two. Yes, the state would have operating costs with us that they don’t have at Sears Island, but maybe there is a much more higher up front cost to build it and the two offset each other.”

What’s in it for Sprague?

“We would lease a property that has a dedicated gate, it’s 100 acres and would be all the state’s, so any grants that come out would go to the state,” he said. “We would get a lease payment. That’s where it ends. We’re not obligating the state to use our labor in any way. What I would assume, as the state being a port authority, they’d have to come out with an RFP for any services to run the terminal.”

With that scenario, Therriault said Sprague did not know if it would bid on operating the terminal.

“For us, we look at it as we are giving up almost half our terminal and the future capabilities of that in exchange for some guaranteed lease payments for a period of time,” he said.

Like Sprague, the state is banking on generating revenue from its real estate.

“Based on similar offshore wind developments, potential lease payments that are likely to be made by offshore wind energy generation companies can be estimated,” the state wrote, in its grant application. “Based on four recent similar lease agreements, payments are estimated between $60,000 and $280,000 per acre per year. Therefore, over a period of 25 years, a 100-acre site is likely to generate between $125 million and $560 million in private sector contributions to the State of Maine as a direct result of the port being constructed.”

Two days after the June 11 Sprague tours, an opinion piece was published in the Bangor Daily News, reciting the advantages of a wind port on Sears Island.

In it, Matthew Burns, executive director of the Maine Port Authority, substantiated the state’s February statement that the, “most feasible and cost-effective location for an offshore wind port in Maine is on Sears Island.”

He wrote that Maine, “objectively and thoroughly considered proposals for Mack Point and found its physical and logistical constraints, need for significant dredging, and increased cost to taxpayers for land leasing and port construction,” would result in an inferior port to that of Sears Island.

Burns wrote there would not be enough room for construction, assembly and launch of turbines, nor would its pier infrastructure be adequate to hold the weight of components on Mack Point.

And, he said, Sears Island would require no dredging.

As Maine awaits word of federal funding, some groups responded to a query about their opinions of Mack Point following the June 11 tours.

The Belfast-based nonprofit Upstream Watch, concluded: “Upstream Watch's position since last fall has been that if an offshore wind port is to be developed in Penobscot Bay, it should be built at the already industrialized Mack Point, not Sears Island,” said Executive Director Jillian Howell. “After being on the ground at the site while listening to Sprague representatives talk through their proposal and what redevelopment of their facility would look like, it is even more clear to us that this is a viable alternative to Sears Island. Why are we considering sacrificing Sears Island in the name of addressing the climate crisis when this wind port can be incorporated into Mack Point?”

Last November, members of Maine’s Energy Office visited Sprague, and were walked through a version of the Sprague plan, he said.

“We know they are aware of the plan, but I think at the end, the DOT is the one making the decisions as to which facility is chosen,” he said. “They are controlling the cards. There is nothing we can do until we see what they do, and we’ll respond accordingly.”

The Environmental Protection Agency Region 1, with offices in Boston, has heard there is an alternative, he said.

“And I would expect that Region 1 of the EPA would want to know more about it,” he said.

Meanwhile, Sprague continues to look at other energy opportunities.

“From a broader context, we’ve always believed that it is appropriate to replace our current forms of energy with cleaner forms of energy,” said CEO David Glendon. “It’s better to displace ourselves than let someone else do that for us. We have had a long history of pursuit of cleaner forms of energy, including current efforts.”

That includes wood-chip produced renewable diesel, equipping fuel tanks in South Portland with solar panels on the roof, and turning waste products to produce natural gas in New Hampshire, he said.

“All of these are consistent with the energy transition that is happening,” he said. “Just like we’ve seen it happen over the last 200 years, where we have replaced coal with oil, and oil with natural gas, and now those biofuels. We see ocean wind as a big component of that, as well. It is going to come at some point in time.”

Reach Editorial Director Lynda Clancy at lyndaclancy@penbaypilot.com; 207-706-6657