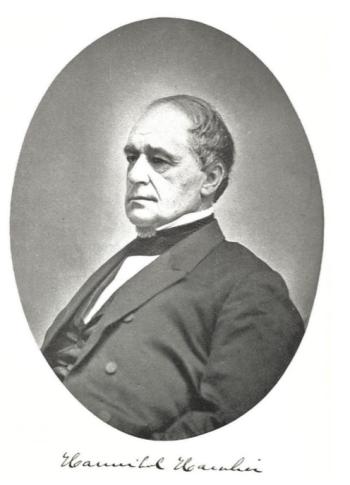

Ann Morris writes about her new hero: Lincoln’s Vice President from Maine

Challenges of Hannibal Hamlin’s days are like challenges of today. Hamlin faced the challenges of his time with optimism and service to his country. He believed that every age grew better as it grew older; and he believed that every age produced strong men to solve its problems.

A rare biography of Hannibal Hamlin, The Life and Times of Hannibal Hamlin, 1809-1891, written in 1899 by Hamlin’s grandson, Charles E. Hamlin, is full of great stories, and shows how leaders dealt with divisions like those of today. What follows is a summary of those stories to make us proud of our Civil War Vice President from Maine.

Hannibal Hamlin was born in August of 1809 in Paris Hill, on the crest of a foothill of the White Mountains of Western Maine, overlooking the Androscoggin Valley. A local Indian described the area at sunset as “the smile of the Creator.”

Hannibal’s father, Dr. Cyrus Hamlin, was born at Harvard and attended medical school there. His mother was Anna Livermore whose father founded the town of Livermore, Maine. Dr. Hamlin specialized in children’s medicine, and children loved to follow him home and sit on his porch swing to hear him tell stories. Dr. Hamlin built a large Greek Revival mansion on the village common in Paris Hill and served as sheriff of Oxford County.

Hannibal was the sixth of seven children, a popular boy – smart, athletic, warm-hearted, and charismatic. He loved hunting and fishing and the game that became baseball. He was seven years old when Andrew Jackson won the Battle of New Orleans, during the War of 1812, and Jackson became one of Hannibal’s greatest heroes.

Dr. Hamlin was one of the founders of Waterville College, which became Colby College, and he sent Hannibal to Hebron Academy to prepare for college. But when his older brother, Cyrus, became ill, Hannibal had to return home to run the family farm. Living at home when Congressman and then Governor Enoch Lincoln was living with the Hamlins, gave Hannibal a strong interest in the law and politics. Lincoln was a leader of the anti-slavery movement in Maine. By age twenty, Hannibal had found time to own a local newspaper and study law.

In 1832, Hamlin moved to Portland to study in the law office of Fessenden & Deblois. General Samuel Fessenden, a senior partner, was the father of William Pitt Fessenden, a US Senator from Maine during the Civil War, and Samuel Clement Fessenden, the first pastor of the Rockland Congregational Church and a member of the US Congress during the Civil War. General Fessenden was a strong abolitionist, especially after the British Parliament abolished slavery in 1833.

In 1833, Hamlin returned to Paris Hill and married Sarah Emery. They moved to Hampden, just below Bangor on the Penobscot River, where Hamlin opened a law office. He was such a popular speaker with a ready wit, that crowds came to hear him try a case. He served in the state legislature for five years when Jonathan Cilley of Thomaston was Speaker of the Maine House. While in the state legislature, Hamlin became Speaker of the Maine legislature when he was only 28 years old.

Hamlin was elected to the Congress in 1843, campaigning on the issue of requiring the railroads to charge less for carrying the US mail. Congress was contentious during Hamlin’s tenure, and many congressmen carried pistols. During his four years in Congress, the issues dealt with included: providing a pension for elderly veterans of the American Revolution, annexation of the young republic of Texas, outlawing dueling after the death of Congressman Jonathan Cilley of Thomaston, and the Wilmot Proviso – trying to establish the northern boundary of Oregon and make the territories of Oregon and Texas states.

Hamlin was elected to the US Senate in 1848 and served along with Henry Clay, John C. Calhoun, Daniel Webster, Jefferson Davis, and Thomas Hart Benton. Grandson Charles Hamlin wrote in 1899: “At no time, before or since, in the history of the Senate, has it membership been so illustrious, its weight of character and ability been so great.”

Southerners wanted to be able to move with their slaves into any territory, and that made negotiations for statehood for Oregon, Texas, Arizona, New Mexico, and California difficult. The Wilmont Proviso brought Oregon and Texas into the Union – one free and one slave. Then when gold was discovered in California, enough men rushed there to make the population large enough to apply for statehood. The people of California formed a government and applied for statehood as a free state. Southern leaders wanted California to be divided in the middle and join the Union as one free state and one slave state.

Henry Clay designed the Compromise of 1850 to: admit California as a free state, create the Territory of New Mexico, create the Territory of Utah, require the return of fugitive slaves, and prohibit bringing slaves into the District of Columbia for transportation or for sale. Senator Hamlin spoke eloquently in favor of California’s admission as a free state.

As a member and then chairman of the Senate Committee on Commerce, Hamlin promoted shipping interests, customs services, river and harbor improvements, the life-saving department, and coast surveys. He introduced a bill to license steamboats for safety and a bill to require owners to register their vessels.

After the repeal of the Missouri Compromise in 1854, the Democratic Party became solidly pro-slavery throughout the country. Hamlin threatened to leave the party, but then had to return to Hampden, Maine, to care for his wife who died in April of 1855. Senators and constituents begged him not to resign from the Senate.

In spite of the possible war with Spain over Cuba and Britain’s attempts to involve Americans in the Crimean War, Americans focused on the Kansas Nebraska Act. President Franklin Pierce called a special election for the people of Kansas to choose a delegate to Congress. Ruffians from Missouri came with guns to stuff ballot boxes with pro-slavery candidates. President Pierce removed Andrew Reeder, governor of the territory, because Reeder tried to stop the mobs; and then Reeder was elected to Congress. Hamlin returned to Washington at this point. The slavery conflict had intensified in Washington and led to the caning of Senator Charles Sumner.

When the Democratic Party indorsed the repeal of the Missouri Compromise and nominated pro-slavery James Buchanan for president, Hamlin left the Democrats, saying: “I love my country more than I love my party;” and he joined the new Republican Party. He considered it the most important act of his life, and he took the entire state of Maine with him. Politicians of Maine wanted Hamlin to run for governor, but Hamlin did not want to give up his seat and his vote in the Senate.

Delegates to the first Republican National Convention, in 1856, in Philadelphia wrote a platform that sought to extinguish slavery and polygamy in the territories. Delegates proposed Hamlin to be the first Republican candidate for president. Hamlin hurried from Washington to Philadelphia to withdraw his name from consideration; and John C. Fremont became the nominee.

The first act of the Republican Party in Maine was to elect Hannibal Hamlin governor in 1856. In his acceptance speech he promoted the teaching of agricultural science in the schools. The same week that Hamlin became governor of Maine, the Republican legislators nominated him for another term in the Senate. He resigned as governor in February of 1857 and resumed his seat in the Senate.

James Buchanan was elected president, in 1856, and asserted that the slavery troubles were over. But right away the Supreme Court decided the Dred Scott Case – declaring that a Negro could not become a citizen because he was chattel, and Congress could not interfere with slavery in the territories. In 1859, after several bloody skirmishes, the citizens of Kansas voted for a state constitution that had Kansas enter the Union as a free state.

In 1860, the Republican National Convention was held in Chicago. Many delegates, especially those from Maine, wanted Hamlin as their candidate for President or Vice President, but Hamlin declined, thinking he belonged in the Senate. Hamlin was shocked when men came to his Washington hotel room to tell him that he had been chosen to run as Abraham Lincoln’s Vice President.

Upon winning the election in November, Lincoln invited Hamlin to meet him in Chicago. There he told him, “Mr. Hamlin…I shall always be willing to accept, in the very best spirit, any advice that you, the Vice President, may give me.” Lincoln shared his thoughts about cabinet members and asked Hamlin to recommend someone from New England to be Secretary of the Navy.

As Southern states seceded from the Union, Lincoln proceeded cautiously, hoping the border states would stay in the Union and war could be avoided. Hamlin thought war was inevitable. After Fort Sumter was attacked, Hamlin thought no man ever grew in his lifetime as Lincoln did. Hamlin recruited many soldiers from Maine, and Maine furnished more troops than any other state in the Union.

President Lincoln invited Vice President Hamlin to become a consulting member of the Cabinet, and Hamlin accepted. But he soon realized that he had no authority in the Cabinet, and he limited his influence in government affairs to his personal friendships, which were many. He was especially Lincoln’s friend and trusted counselor.

From the beginning, Hamlin was a radical in favor of emancipation and arming the Negroes. Lincoln was tentative, still hoping to save the Union. When Lincoln decided that emancipation was inevitable, Hamlin was the first person with whom he shared the draft of his proclamation, after a supper together on June 18, 1862. After the slaves in the Confederate states were emancipated in 1863, Hamlin introduced Lincoln to enlisted officers from Maine, including his sons Charles and Cyrus, who were willing to command colored troops. Lincoln was impressed, and Hamlin persuaded him to order the Secretary of War to form a brigade of colored troops. Secretary Stanton had long been in favor of this, and he was overjoyed.

But during the midterm elections of 1862, before Lincoln announced his Emancipation Proclamation, with a blockade of shipping to and from the South, and just after he announced the draft; the Republican party lost support. Hamlin campaigned vigorously in support of Republicans and in support of the war. Hamlin was one of the first to lose confidence in General McClellan. Hamlin recommended McClellan be replaced by someone like Ulysses S. Grant, Joseph Hooker, or local Rockland hero Hiram G. Berry. In The Life and Times of Hannibal Hamlin, 1809-1891, Charles Hamlin wrote:

“The man in whom Mr. Hamlin was most interested, and whose fortunes he served

to advance most, was Hiram Gregory Berry, of Rockland, Maine. At the outbreak

of the war, Berry was a Breckinridge Democrat, but he was one of the first of Maine’s

men to enlist. Mr. Hamlin had never met Berry until the war began, but when he saw

this soldierly, massive, and lion-hearted man, he took to him at once, and in this

instance his intuitions were correct. Berry had always been interested in military

affairs, and when Sumter was fired on, he set to work organizing the Fourth Maine

Infantry. He was a born soldier and leader of men, and the regiment elected him

their colonel. Both he and Jameson of the Second Maine won a national reputation

by their fine work at Bull Run, and both attracted the attention of the administration.

Berry’s positive fighting genius was recognized, and in April, 1862, he was appointed

brigadier-general, and in January, 1863, a major-general of volunteers. Mr. Hamlin, it

is needless to say, induced President Lincoln to promote General Berry. But he was

killed at Chancellorsville at the front of his division, and Hooker, who loved and

appreciated Berry, said: “There lies the man who should have succeeded me as the

commander of the Army of the Potomac.” Stanton also told Vice President Hamlin

that Berry had been selected as Hooker’s possible successor. He was one of the

noblest soldiers Maine produced, and seemed destined for a shining career.”

During the war, when he learned that soldiers from Maine were in the hospital dying of dysentery, Hamlin left his office in the Senate and hurried to their bedsides to see that they had the care they needed and to talk and cheer them like a tonic. He got soldiers who had been in Confederate prisons their back pay. Hamlin also campaigned against the Copperheads in the North who wanted to end the war without emancipating the slaves so they could pursue their shipping interests in the South.

At the Republican National Convention in Baltimore, in 1864, the delegates renominated Abraham Lincoln to run for a second term and chose Andrew Johnson of Tennessee to run to be his Vice President. Lincoln was very disappointed, but in those days the candidate, even if he was President, had no say in who his running mate would be.

On March 4, 1865, the day Johnson was to be inaugurated, he appeared at Hamlin’s office, drunk; and after a brief conversation, asked for some whiskey. Hamlin had outlawed whiskey in the Senate, and he sent a messenger to purchase some. Johnson drank most of the bottle. Hamlin guided Johnson to the Senate chamber, gave a valedictory address, and introduce Vice President Johnson. Johnson made a miserable spectacle of himself, giving an incoherent, maudlin, drunken harangue. As senators covered their faces in embarrassment, President Lincoln entered the chamber, and Hamlin was able to administer the oath of office and lead Johnson off the stage.

Hamlin went home to Maine and said that when he entered politics, he “spoiled the making of a good farmer.” On April 9, 1865, General Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox; and on April 14, five days later, President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated. On the morning of April 15, Mr. Hamlin walked into Bangor to read the news on the newspaper bulletin board. With tears streaming down his cheeks, all he could say was, “He was a great man.”

He worked hard that year to establish the Maine College of Agriculture and Mechanical Arts which would become the University of Maine. As the first President of the Board of Trustees, he saw to it that the state school was located at Orono.

He left that post to take the lucrative job of Collector of the Port of Boston in August of 1865. But he resigned one year later because he did not want a patronage job from President Andrew Johnson.

Hamlin led the campaign, speaking publicly, for Johnson’s impeachment. Johnson had abandoned the freed slaves; he was trying to rehabilitate the Southern secessionist leaders; and he proposed that the government repudiate its debt. Hamlin declared it was unconstitutional for the President, rather than Congress, to decide the procedure for rebel states to rejoin the Union.

Johnson was impeached by the House, but escaped conviction by the Senate by one vote. The great disappointment of Congress gave Hamlin a peculiar hold on the affections of his party. He was often introduced, to his great annoyance, as the man who should have been president.

After this disappointment, Hamlin wasted no time. As soon as he relinquished the collectorship in October of 1866, he turned to the building of a railroad in Maine. He was elected president of the company that built a railroad from Bangor and Old Town to Dover and Moosehead Lake.

And then in 1869, Hamlin ran for the Senate. It was a close race against an incumbent senator, but Hamlin won because Maine wanted to show its disapproval of President Johnson.

Hamlin entered the Senate with a new generation of leaders and new issues as well as old. He was convinced that the spirit of unrest which followed the war was responsible for the poor reputation of President Ulysses S. Grant’s administration, and he considered Grant a greater statesman than he was credited with being. Hamlin was pleased when Hiram Revels, a black man, replaced Jefferson Davis as a Senator from Mississippi. He believed the world grew better as it grew older, and he believed that every age produced strong men to solve its problems.

Hamlin served as chairman of the Committee on the District of Columbia and was instrumental in securing the funding necessary to transform the straggling, dirty city into a beautiful, healthy city. As chairman of the Committee on Post Offices and Post Roads he advocated for raising rates for transmitting merchandise and newspapers through the mail and for reducing the cost for letters to a two-cent stamp. When someone from Kendall’s Mills, Maine, wrote to Hamlin and another member of the Maine delegation requesting a charter to start a national bank, the other delegate wrote that the charter could not be obtained. Hamlin’s response arrived the same day and contained the charter, itself.

The presidential election of 1876, between Republican Rutherford B. Hayes and Democrat Samuel J. Tilden, was severely contested. Federal troops supported the Republicans, and the Ku Klux Klan supported the Southern Democrats, leading to fraud, intimidations, and violence from both sides. The election was held on November 7, 1876, and when the electors met on December 6, three states – South Carolina, Louisiana, and Florida – each submitted two sets of electors. The Constitution did not indicate whether the President of the Senate or the total membership of Congress should decide which votes to count.

Negotiations ensued. The Southern Democrats wanted federal troops withdrawn from the south; they wanted to revive their ties with conservative Northern businessmen; and they wanted federal support for Southern railroads like that given to the North. An electoral commission was established to determine which electoral votes to count. Hamlin was against establishing the commission because he thought it set a dangerous precedent.

Both houses of Congress began counting the electoral votes on February 1, 1877, with the electoral commission deciding which electoral votes to count from the three states that had two sets of electors. Tilden Democrats threatened to filibuster. Hayes and the Republicans negotiated – promising to withdraw federal troops from the South, appoint a Southern Democrat to the Cabinet, and consider federal support for southern infrastructure improvements such as a railroad. The vote count was completed on March 2, 1877. Hayes won by one electoral vote, and he was inaugurated on March 5, 1877. President Hayes bragged, “Gentlemen, I expect as a result of my Southern policy that the Republican Party will carry six or seven states in the next election.” Hamlin responded, “Mr. President, you will not carry a single school district.” Hamlin’s prediction was confirmed by the growth of the solid South.

Hamlin campaigned against the evils of the patronage system and for the creation of Civil Service Reform. As chairman of the Committee on Foreign Relations, he worked on the negotiations with Great Britain regarding the North Atlantic fisheries, and he worked against the Chinese Exclusion Act which was not passed until 1882. Hamlin retired from the Senate in 1880.

Hamlin participated in the Republican National Convention of 1880, supporting Ulysses S. Grant for a third term as President. Grant was seen as the one to protect the rights of Southern Republicans. James A. Garfield received the Republican nomination and won the presidential election.

Just before retiring from the Senate, Hamlin mentioned that he would like to visit Europe. Upon hearing that, President Garfield offered to appoint Hamlin minister to Germany, Italy, or Spain. Hamlin accepted the appointment to Spain on the condition that he could resign after one year. He found the Spanish people courteous but proud and unprogressive. Hamlin traced the decadence of Spain to the expulsion of the Moors, who were its ablest and most progressive element.

Upon his retirement, Hamlin entered the social life of Bangor with zest, enjoying his neighbors and his little farm. He spoke at campaigns, attended Grand Army of the Republic encampments, fished, read, and traveled. He enjoyed dancing, card-playing, and the theater. He was liberal in his faith, and for some years, served as president of the Unitarian Society of Maine. He also loved poetry, Shakespeare, and children.

His last important public act was to urge the nation to make Lincoln’s birthday a national holiday. He began his campaign in 1887 by writing a letter to the Republican Club of New York to be read at its Lincoln Dinner. In February of 1891, Hamlin traveled to New York for the Lincoln Dinner at the Republican Club. The venerable statesman, the anti-slavery leader, one of the fathers of the Republican Party, spoke in support of making the birthday of Abraham Lincoln, his trusted friend and “one of the greatest men the world has ever known,” a national holiday. Men cheered and wept as he left the hall. He stood in the doorway, lifted his hands, and said, “Good-bye. God bless you all.” Five months later, in July of 1891, Hamlin’s heart gave out during a card game.

By the time his grandson wrote the biography of Hamlin in 1899, the movement to nationalize Lincoln’s birthday had been passed by the legislatures of Illinois, New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and Washington.