Samizu Matsuki, obituary

Samizu Matsuki, an award winning Japanese artist who retired to the Penobscot Bay region of Maine in 1993, passed away in her Rockland home on August 4, 2018 . A classical realist oil painter, Samizu played a brief yet important role in reaffirming the legitimacy of realistic oil painting as High Art in the New York City painting scene of the early 1970s, drawing huge crowds to her entries at several national and international competitions. Samizu's significance is in her returning the techniques of Western Classical Realism painting, as filtered through Japanese art schools since the 19th Century, back to the West.

She was born March 16, 1936 in the town of Uryu in Hokkaido, Japan, to educators Masue and Satoru Matsuki. Samizu was introduced early to western culture by her parents. The works of western influenced Japanese artists Ryusei Kishida and Kuroda Seiki were particularly influential.

The family lived in a number of locations on Hokkaido, finally the resort town Noboribetsu, famed for its scenery and hot springs. Samizu's lineal ancestors had moved to southern Hokkaido in the late 19th Century.

Her parents' and their friends' embrace of western culture and their adoption of pacifism in opposition to the Japanese War led to persecution. One of Satoru's friend was tortured to death. Satoru, who was also in poor health, went into hiding for the rest of that conflict. The children at school put Samizu down, due to her father being a pacifist. Whenever he secretly came home, she had to look at the floor so she couldn't say she saw him, when asked by school offcials

The hot springs not being a war target, Samizu and her siblings and parents were spared the destructive warfare meted out elsewhere, during World War II. One of her early recollection of the war was as a 9-year-old sitting on a Noboribetsu hilltop with her sister, when a U.S. bomber flying low to a bombing destination down the Hokkaido coast flew past her. The pilot grinned and waved and, startled, she waved back. He disappeared over a ridge, and a moment later there was a boom! as a harbor target was attacked.

After the surrender of Japan, her father's pacifist history resulted in his being given a number of important educational leadership posts, where he applied the innovations of American educator Ruth Benedict and philosopher John Dewey to the reforming of Japanese educational system, earning him an award from Emperor Hirohito in 1970.

Samizu's second experience of Americans was when she was 10. A convoy of them drove to her town for the first time. They were tall, in dress uniforms,with white gloves and shiny shoes, and polite!

Samizu's early drawing and painting prodigality won her a full scholarship to Joshibi University in Tokyo, then known as the National Women's College of Fine Arts. She would be the first in her family to move to Tokyo from their rural Hokkaido town.

At the college, Samizu first studied under painter Setsuko Migishi, then moved on to the study of western artists. Her graduation work “Daphne (oil, approximately 4' by 5'), suffered some notoriety for its sensuality; briefly pulled from view at during its first showing, it mysteriously reappeared on the display wall the next morning.

Her two teaching jobs, one at an elementary school in Itabashi Precinct in 1959, the other at Shimura Daisan Junior High School in Tokyo in 1961, illuminated for her the malleability of children as expressed by scholar Herbert Reade's book Education Through Art.

An active member of the Tokyo Teachers Union, in 1960 Samizu gave a presentation and lecture in the swank Bunkyo Precinct in Tokyo, where, speaking on behalf of the teachers of the working class Itabashi precinct, she called for adoption throughout the Japanese educational system of the principles laid out in Reade's book and encouragement of originality and creativity among pupils.

In an abrupt change, in 1961, Matsuki married American airman Herman Berry at the American Embassy in Tokyo. They left Japan in 1962, and for the next seven years lived at airbases in Europe and the United States. During this time Samizu painted numerous portraits in Appalachia and at Spangarlem air force base in Germany where she painted Air Force officers and their wives, and a recently deceased USAF fighter ace.

When her husband was sent to a base in Pakistan, Samizu spent a year and a half in Appalachia with Herman Berry's family. Her father-in-law was an itinerant but successful singing preacher, with a congregation in their remote Appalachian mountain community of Valdese in western North Carolina.

Of that time she writes: "Those 18 months in North Carolina were perhaps the most memorable time I have spent in the U.S. This enclave of rural life, which was something I had not expected to encounter in America the Spearhead of the Modern Times, gave me a rich experience in human life."

In 1969, Samizu divorced Berry and moved to Albany, Oregon, where she helped set up the Albany Art Center, and submitted the winning design for the logo of the 1969 Albany Jaycees Timber Carnival, before moving to New York City.

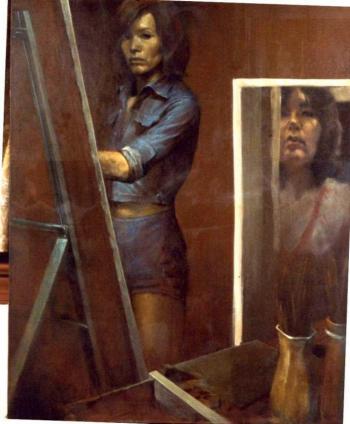

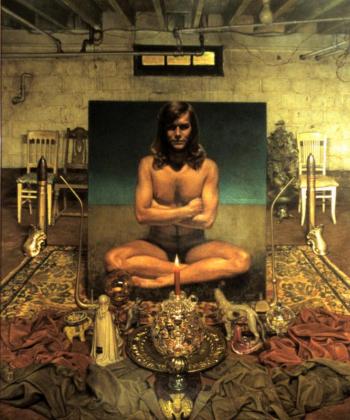

There she plunged into the fine arts cultural scene. By 1975, her explorations of classical realism had won her a gold medal at the 1970 First New York International Art Show (Triumphal Return), membership as the first woman artist accepted by the prestigious and hitherto men-only Salmagundi Club, the Grand Prix at the 1971 Locust Valley Art Show on Long Island, New York, for “A Celebrator” , and the Award of Excellence at the 1974 Abraham & Straus-Hempstead Art Show, "Long Island Art '74" for “AH!”.

Uncomfortable in the dog-eat-dog competitive art world, Samizu left New York but continued to paint. Now it became a profession. Over the next two decades, she painted dozens of landscapes, portraits and still lifes, spending sometimes as few as four hours on a painting, rather than four months as with Triumphal Return. She lived in California for a time. While there, Matsuki painted an ocean scene mural in Santa Barbara, California.

In 1985 Samizu met Earth First! Activist Ron Huber. She prepared a cover drawing for the Earth First Journal showing Huber defying two sheriff's deputies high in an old growth tree.

Chronic injuries and illness, particularly long-undiagnosed Lyme Disease, put an end to her professional career, though she subsequently painted numerous more modest works, mostly portraits. Samizu's eyes failed; her works became darker.

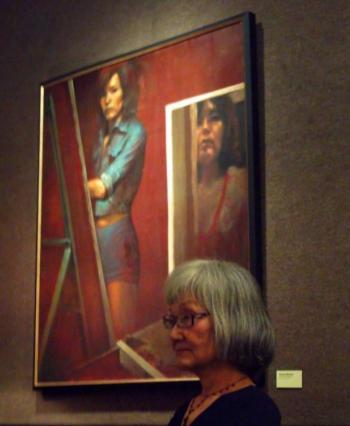

Samizu was honored in 2012 by the Salmagundi Club for being a “Pioneer Woman” — first female in the century-old artists' club.

On September 1, 2017, Samizu was severely burned in a freak accident. Rescued by neighbor Lori Tinker, she went through extensive surgery and physical therapy, but nonetheless weakened, as cancer suddenly took hold of her kidneys. She died early on the morning of August 4, 2018.

Samizu's 1970s works aided in relegitimizing realistic oil painting as a practiced high art form, challenging the then-dominant expressionist paradigm, which Tom Wolfe pilloried in his book The Painted Word.

Samizu is survived by her 33-year partner Ron Huber, her brothers Madoka Matsuki and Arata Matsuki, and her sisters Fumi Raith, Ibuki Nagano and Masue Sato. For more about Samizu Matsuki visit her wikipedia page.